Data-center owners and operators face increasing complexity and operational challenges as they look to improve IT resiliency, build out capacity at the edge, and retain skilled staff in a tight labor market.

Meanwhile, use of the public cloud for mission-critical workloads is up, according to Uptime Institute, even as many enterprises seek greater transparency into cloud providers’ operations.

These are some of the highlights of 2021’s Global Data Center Survey, which tracks trends in capacity growth, capital spending, tech adoption, and staffing.

Fewer data center outages, higher costs

In its annual survey, Uptime looks at the number and seriousness of outages over a three-year period. In terms of overall outage numbers, 69% of owners and operators surveyed in 2021 had some sort of outage in the past three years, a fall from 78% in 2020. Uptime notes that the improvement in the number of outages could be traced to operational changes driven by the pandemic:

“The recent improvement may be partially attributed to the impact of COVID-19, which, despite expectations, led to fewer major data-center outages in 2020. This was likely due to reduced enterprise data-center activity, fewer people on-site, fewer upgrades, and reduced workload/traffic levels in many organizations—coupled with an increase in cloud/public internet-based application use,” Uptime reports. (Related: COVID-19 best practices for data-center operators)

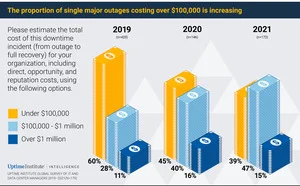

In terms of seriousness of outages, roughly half of all data center outages cause significant revenue, time, and reputational damage, according to Uptime. In this year’s report, 20% of outages were deemed severe or serious by the organizations that reported them. Roughly six in 10 major outages in the 2021 survey cost more than $100,000.

Power remains the leading cause of major outages, responsible for 43% of outages in 2021, followed by network issues (14%) cooling failures (14%), and software/IT systems error (14%).

More mission-critical workloads in the cloud

Data-center owners and operators are increasingly moving mission-critical workloads to a public cloud, Uptime finds, although visibility issues persist for some cloud users and would-be users.

When asked if they place mission-critical workloads into public clouds, 33% of respondents said yes (up from 26% in 2019) and 67% said no (down from 74%).

The “yes” respondents were split between those that say they have adequate visibility into the operational resiliency of the service (18% of all respondents), and those that don’t think they have adequate visibility (15%).

The “no” respondents were also divided: 24% said they would be more likely to put mission-critical workloads into public clouds if there was a higher level of visibility into the operational resiliency of the service, while 43% said they don’t place mission-critical workloads into public clouds and have no plans to do so.

“Cloud companies are beginning to respond to the requirement for better visibility as part of their efforts to win over more large commercial customers. This trend toward improved access and auditability, still in its early days, will likely accelerate in the years to come, as competition and compliance requirements increase,” Uptime says.

Despite concerns about visibility and operational transparency, 61% of respondents that have their workloads spread across on-premises, cloud and colocation sites believe that distributing their workloads across these venues has increased their resiliency. Just 9% think their organization has become less resilient using these architectures. 30% said they don’t know.

Public-cloud repatriation not happening for most enterprises

What goes in the cloud tends to stay in the cloud, Uptime’s research shows.

When asked if they had repatriated any workloads or data from a public cloud to a private cloud or private on-prem/colocation environment, nearly 70% said no. Among the 32% of respondents who said yes, the most common primary reason for repatriation was cost, followed by regulatory compliance. Other reasons included performance issues and perceived concerns over security. Actual security breaches were responsible for just 1% of repatriated workloads, according to Uptime.

“When organizations deploy in a public cloud, their workloads typically remain there, despite speculation about an imminent wave of cloud repatriation,” Uptime concludes.

Edge expansion continues

Most respondents expect to see demand for edge computing increase in 2021: 35% of respondents said they expect edge-computing demand to somewhat increase, and another 26% expect demand to significantly increase.

Looking ahead, the largest percentage of respondents (40%) expect to use mostly their own private edge data-center facilities for the coming buildup, followed by 18% who expect to use a mix of private and colocation. The remainder plan to rely mostly on colocation (7%), outsourcing (3%), or public cloud (2%).

Uptimes notes those plans may change over time: “Yet it is still early days for this next generation of edge buildout, and expectations are likely to change as more edge workloads are deployed. Shared facilities may well play a larger role as demand grows over time. In addition to improved business flexibility and low capital investment, the benefits of shared edge sites will include reduced complexity compared with managing multiple, geographically dispersed sites.”

Staffing problems persist

The struggle to attract and retain staff is an ongoing problem for many data-center owners and operators. Among respondents, 47% report difficulty finding qualified candidates for open jobs, and 32% say their employees are being hired away, often by competitors.

In the big picture, Uptime projects that staff requirements will grow globally from about 2 million full-time employee equivalents in 2019 to nearly 2.3 million in 2025.

According to Uptime: “New staff will be needed in all job roles and across all geographic regions. In the mature data-center markets of North America and Europe, there is an additional threat of an aging workforce, with many experienced professionals set to retire around the same time—leaving more unfilled jobs, as well as a shortfall of experience. An industry-wide drive to attract more staff, with more diversity, has yet to bring widespread change.”

Data-center environmental practices lag

The notion of sustainability is growing in importance in the data-center sector, but most organizations don’t closely track their environmental footprint, Uptime finds.

Survey respondents were asked which IT or data-center metrics they compile and report for corporate sustainability purposes. Power consumption is the top sustainability metric tracked, cited by 82% of respondents. Power usage effectiveness (PUE), a metric used to define data-center efficiency, is close behind, tracked by 70% of respondents.

Many data centers consume large volumes of water, Uptime says, but only about half of owners and operators track water use. Even fewer respondents said they track server utilization (40%), IT or data-center carbon emissions (33%), and e-waste or equipment lifecycle (25%).

“…[I]t is still common at smaller and privately-owned enterprise data centers that the electric utility bill is paid by property management, which may have little interest or say in how the compute infrastructure is built or operated. This disconnect could explain why most still do not track server utilization, arguably the most important factor in overall digital infrastructure efficiency,” Uptime reports. “Even fewer operators track emissions or the disposal of end-of-life equipment, which underscores the data-center sector’s overall immaturity in adopting comprehensive sustainability practices.”

Other highlights include:

- Organizations are not closely tracking their environmental footprint despite the global sustainability push.

- Job security is strong because the data center skills shortage persists, but AI may reduce staffing needs in the future.

- The number of outages has declined, but the consequences continue to worsen.

- Pandemic pressures and more disrupt data center supply chains.

- Data center suppliers expect large cloud and internet companies to reshape the supply chain.

- Rack density levels are creeping up.

Original article can be found here at Network World.